The oyster’s story

Like lobsters, oysters were once considered cheap eats. They were abundant in the 1800’s, consumed raw and cooked by the working class, served in pies in Britain and as street food in American cities.

When the locomotive came to America, railways allowed fresh oysters from the Chesapeake Bay, Massachusetts and Long Island Sound to be shipped inland, fueling a boom. Voracious harvesting led to overfishing and the near collapse of native stocks by the 1880s, and the price of fresh oysters went through the roof. Not coincidentally, Oysters Rockefeller were invented in 1899 by Jules Alciatore at his family's famous Antoine's Restaurant in New Orleans, where they are still on the menu.

Such a newly valuable crop attracted much experimentation with farming techniques. The Cotuit Oyster Company in Massachusetts, established in 1837, is considered the oldest, continuously operating oyster farm in the U.S., making it a foundational New England aquaculture venture. The term “aquaculture” first appeared in the 1860’s, describing the new seed-to-harvest methodology that would eventually supplant rake-and-culch wild harvesting.

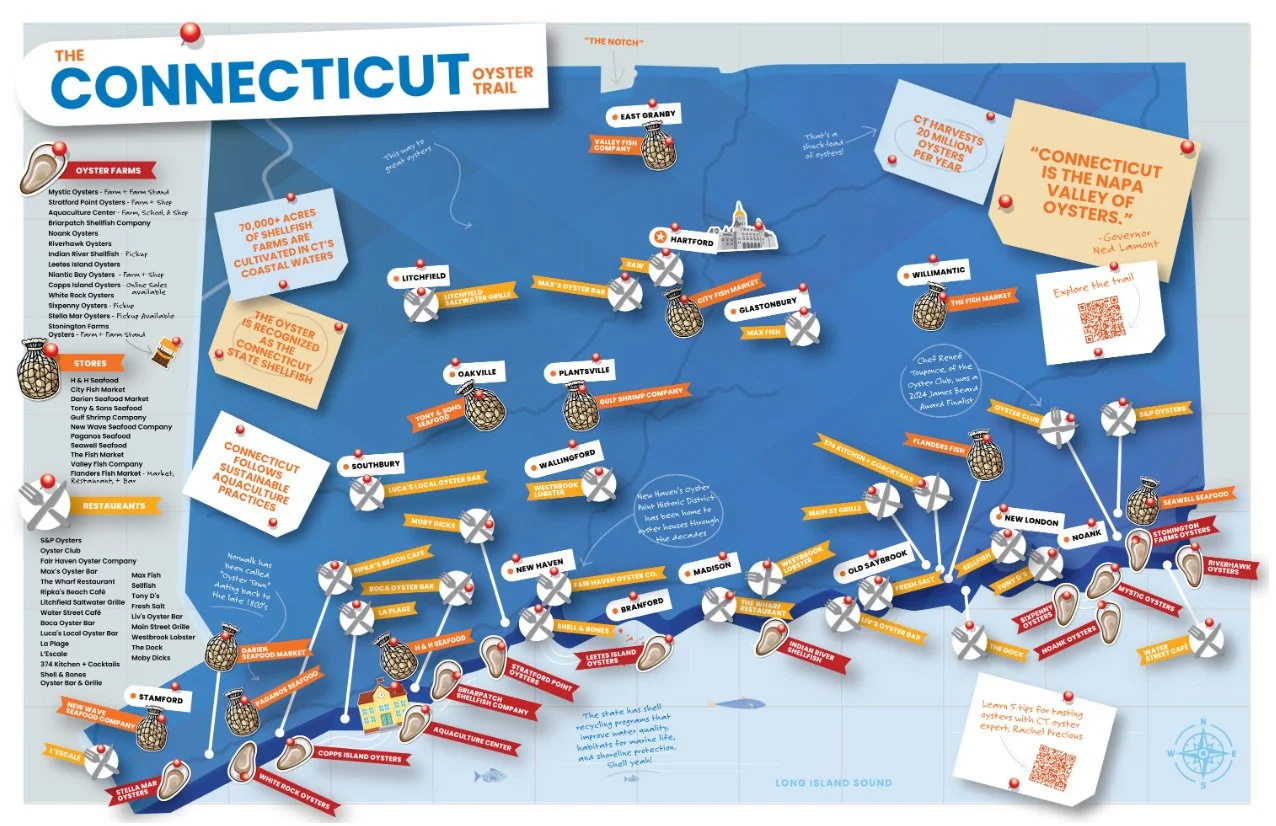

Today, Long Island Sound has thirteen well-established oyster farms and Connecticut harvests some 20 million oysters per year. For a great behind the scenes read, see NOAA Fisheries’ “Long Island Sound's Shellfish Growers are Citizen Scientists.”

Restaurants throughout Connecticut now vie for Oyster Honors (Go Oyster Club!) and CT VISIT even sports a wonderful “Oyster Trail Map” (below, click to enlarge.)

Perhaps the only downside to this historic rebound has been what to do with the huge volume of empty oyster shells left over. Various ideas were floated: grind them up for fertilizer amendments, use them on driveways or in concrete, leave them in the landfill. None were good choices.

Enter Tim Macklin and Todd Koehnke, founders of the Collective Oyster Recycling & Restoration program. The two Fairfield residents (and avowed oyster lovers) saw that other states had developed shell recycling programs. After building a pilot program with the Fairfield Shellfish Commission in 2015, initially collecting shells in their own cars for recycling, they were ready — The pilot worked, and finally in 2023 CORR became a registered non-profit organization to take the program statewide.

How did that work out? Watch this CBS Eye on America profile:

Clearly, the benefits of reusing spent shells are huge, and longterm. While some compare the process to CT’s developing foodscraps-to-compost programs, there is a major distinction: food scraps are a voluntary pay-as-you-throw operation working on a municipal scale, and shell reclamation/restoration is a smaller niche market that does not have an obvious monetization path.

That’s why CORR is presently an environmental non-profit organization dedicated to facilitating a collaborative statewide shell recycling network. At this stage of the game, it’s about scaling up — facilitating as many sources as possible — and that’s where individuals, communities, growers and retailers are helping.

Personal case in point: I’d just started this article when an email came in from a local club asking if I’d help man the oyster shucking table for their annual New Year’s Day bash. I said yes, in part because I knew Stonington Fresh members J&R Seafood and Stonington Farms Shellfish were the suppliers, and because, well, I really like oysters. Tim at CORR asked if I’d like a bucket, and told me where I could borrow one around the back at Oyster Club over the bridge in Mystic. Community at work!

We generated a bucket and a half of shell, though that half bucket went to a local jeweler for creative reuse. The full bucket with its sanitary screwtop lid I put back at Oyster Club, confident that in two years or so the contents would be part of a protective nursery for hundreds more baby oysters. The dozen or so I ate that day never tasted better.

How can you help?